Since much of this philosophical discourse is, well, philosophical and full of conjecture, we mix heroes of the old times, the not-so-old times, and of recent times. We start with a hypothetical bar, let's say at the foot of the Kappelmuur in Geraardsbergen, in the dead middle of February when snow and frost are still on the ground, and add a hypothetical cast of Henri Pelissier, Briek Schotte, Bartali and Coppi, Jacques Anquetil, Eddy Merckx, Freddy Maertens, Bernard Hinault, and of course Greg LeMond.

|

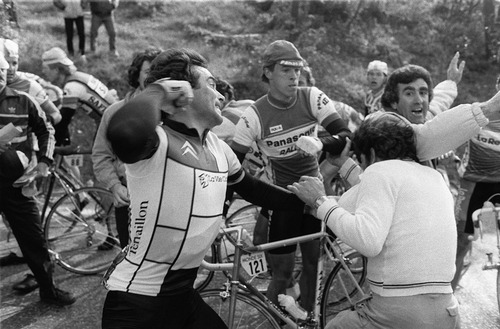

| Bernard Hinault - aka The Badger - demonstrating the usefulness of street fighting skills in Paris-Nice. |

Henri Pelissier

Born in a long-bygone era of fixed gear riding over epic distances, the Pelissier brothers rose to the impossible challenge set by Tour de France organizer Henri Desgrange. As befitting riders of his era, Pelissier is tough as nails, not shy to use every possible means of fighting on, including all sorts of amphetamines, caffeine pills, and strong booze to top it off.

We think Pelissier will have a strong start, what with his various drug-cocktail concoctions he takes regularly, but his cheating ways will catch up to him by the mid-point of the brawl.

Briek Schotte

The original Flemish hardman, Briek Schotte often had to ride to and from races on his own pedal power, turning every 250km classic into epic multi-day adventures.

Born in a time when champions had to rely on donations from fans at the kermesses, lest they suffer nutrition benefits, Briek's compact build may be a disadvantage in a brawl: hide he might, but limited reach will undo him by the half-time.

Gino Bartali

A pious man, who spent the duration of World War II, this hot-headed Tuscan had explosive temper and limitless generosity all residing in the same oversized heart. He doesn't shy from a fight, but his idealism is a serious impediment in a brawl. His inner strength will give him second wind in the final quarter of the brawl, and he might make top five but not quite reach the podium.

Fausto Coppi

Perhaps the antidote to Bartali, Coppi walks like a duck but pedals like an angel. He looks positively awkward on foot. Winner of Roubaix he may be, but he is sure to go down early, perhaps even as unintentional casualty.

Jacques Anquetil

Known first and foremost for his debonair ways, Anquetil lived in the fast lane his entire life. Not content with the stunning platinum blonde Janine, he fathered a child by Janine's daughter from a previous marriage when they all lived under the same roof. However, the reason Anquetil was able to live his life was the relative tranquility of Europe at his time. In a brawl, not much of his skills are actually useful, so we think he'll go down fast and early.

Eddy Merckx

With the nickname "Le Cannibal" it's hard to not bet on Merckx the elder being on the podium, if not finish at the top altogether. This image has stuck in the minds of sophomore-level cycling fans such that Eddy Merckx Cycles even had a series of adverts featuring Tom Boonen's mouth and face dripping with blood.

|

| One in the series of "We're all cannibals" adverts. |

Given all this, we think Merckx would finish on top and not only that, the headlining photograph from the bar fight would be one of him throwing a chair in one direction, clubbing somebody with a beer bottle with his left hand, punching with his right, and kicking another poor sob, all while head-butting yet another poor soul.

Freddy Maertens

Perhaps one of the most naturally talented one-day racer from Belgium, Maertens' career was blighted by bad luck and never-ending rivalry with Eddy Merckx and Roger De Vlaeminck. In particular, for decades Merckx accused Maertens of chasing Merckx down in the finale of the 1973 world championship, while Maertens accused Merck of throwing the race to Felice Gimondi because both Merckx and Gimondi rode Campagnolo while Maertens rode Shimano. Blood feud much?

That said, Maertens is definitely a big gear rider, a factor said to have cut his career short. So surely he has inner strength. But he did push himself into bankruptcy, so he's not the greatest strategic mind. We think Maertens will end up antagonizing too many players very early in the brawl, and when he makes a lunge for Merckx somebody else would trip him up and finish him off.

Bernard Hinault

With his constant scowl, never-say-die attitude, and lightning-fast reflexes (useful for shoving impostors off the Tour de France podium), Hinault exudes self-confidence. His ghost-written autobiography was as simple as can possibly be written: each chapter is a fugue of, "I knew I would win, I won the race, I told you so." On top of all this, Hinault was a charismatic leader of the peloton, perhaps the last true example of Le Patron. His gaze struck fear in the peloton, and he dictated whether a breakaway was to be allowed to even break away in the first place. In a brawl, we suspect he'll gather all the weaker-hearted champions on his side before he stabs them all in the back while scoffing, "I merely do this so that you would be a great champion on your own strength."

Greg LeMond

Exuding Californian youth and sunny exuberance, Greg LeMond's talent shone so brightly that Bernard Hinault and his then-boss Cyrille Guimard flew all the way to court LeMond at his California home. His win at the 1982 Worlds had an air of inevitability to it: here was a young American talent riding for the top French team at that time Gitane-Renault-Elf, and we can't imagine him not wearing the Rainbow Jersey.

Perhaps fitting with that image is his boy scouts-goodliness both in his mannerism and his insistence on saying The Right Thing and doing by The Right Thing. Clearly, LeMond was in awe of his team leader Hinault who lured him to a new team La Vie Claire. Clearly, LeMond truly believed that Hinault would shepherd him to his maiden win in 1986. And very clearly, LeMond felt truly that his trust was betrayed.

But let's put this in perspective. How many pages did Hinault's biography spend to talk about LeMond? Just over one page. If LeMond had had to write a biography upon retirement, how many pages would be spent on Hinault? Probably 80% of the entire biography. So how about that bar brawl? LeMond would have Hinault's back, but Hinault would have LeMond's neck in a heartbeat.

Who do you think would win the bar brawl? Share your thoughts here.

YOOOOOO! Lemond was second in 82 and 85, first in 83 and 89.

ReplyDelete